In a series of previous posts, I have argued that history teachers portraying sentence starters such as ‘I believe…’ and ‘explaining’ connectives such as ‘so’, ‘therefore’ or ‘because’ as ‘the language of the historian’ is misleading. I tried to demonstrate how, far from being ‘how historians write’, such frames at best limit students’ scope to construct their own historical arguments. At worst, some might be fundamentally anti-historical.

Continuing this theme, in this post I want to consider ‘paragraph starters’ such as;

‘One reason why…’

‘Another reason why…’

‘A final reason why…’[i]

By including ‘reason why’ these starters seem most appropriate for arguments constructed in response to questions focused on the second-order concept of causation. Presumably, they could be tweaked to be applicable to other conceptual focuses; perhaps ‘Another reason why Cromwell was significant was…’ for significance or ‘A final difference between the nobility and the gentry was…’ for similarity and difference. For now, however, let us assume that in these frames ‘reason’ operates synonymously with ‘cause’. An example of a causal question that the frames might be used in response to could be;

How far does the role of Governor Phips explain the end of the Salem witch hunt (1692–93)? [ii]

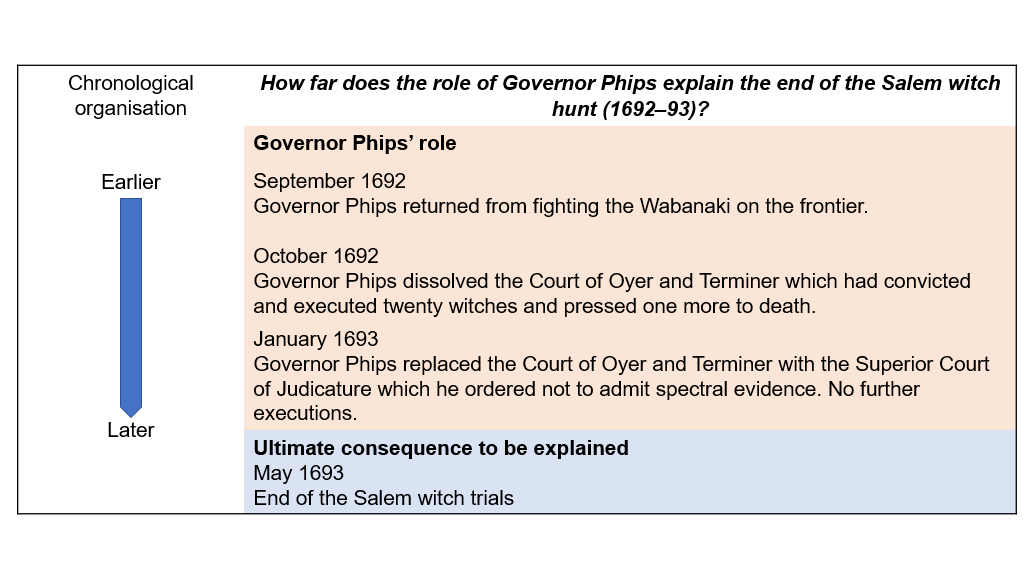

In this question, the student would first be expected to recognise the cause given and argue its relative importance. For example, they might consider how upon returning from fighting the Wabanakis on the frontier in September 1692 Phips closed the Court of Oyer and Terminer which had admitted spectral evidence contributing to a 100% conviction rate. Phips then established the new Superior Court of Judicature in its place which did not admit this type of evidence and therefore predominantly acquitted.

The students would then be required to argue whether other causes which contributed to the craze subsiding were more or less important. Although it is an interpretation which has been rather debunked by more recent research, a traditional cause given for the hunt coming to an end was the ‘afflicted’ girls’ ‘overreaching’: their accusing of those in positions of power including, perhaps, Phips’ own wife. Fearing that the girls might now turn their ferocity on them, powerful male societal gatekeepers removed their endorsement of the girls’ claims. In this staunchly patriarchal society, the girls’ accusations ceased to carry weight once shorn of this legitimation.

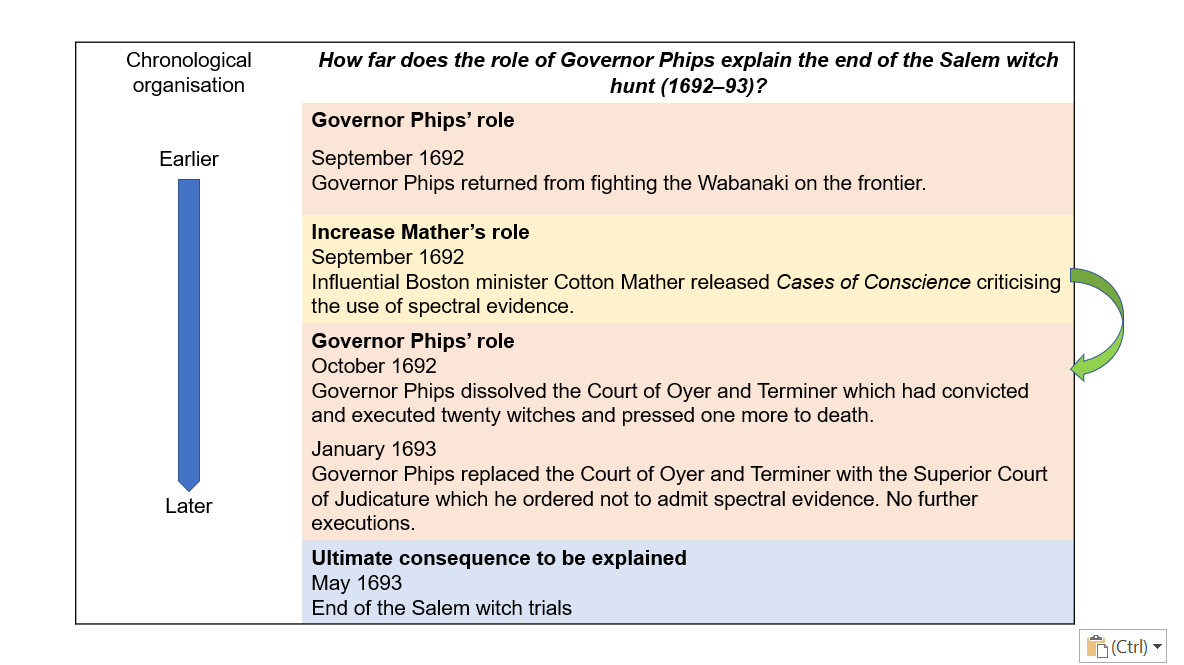

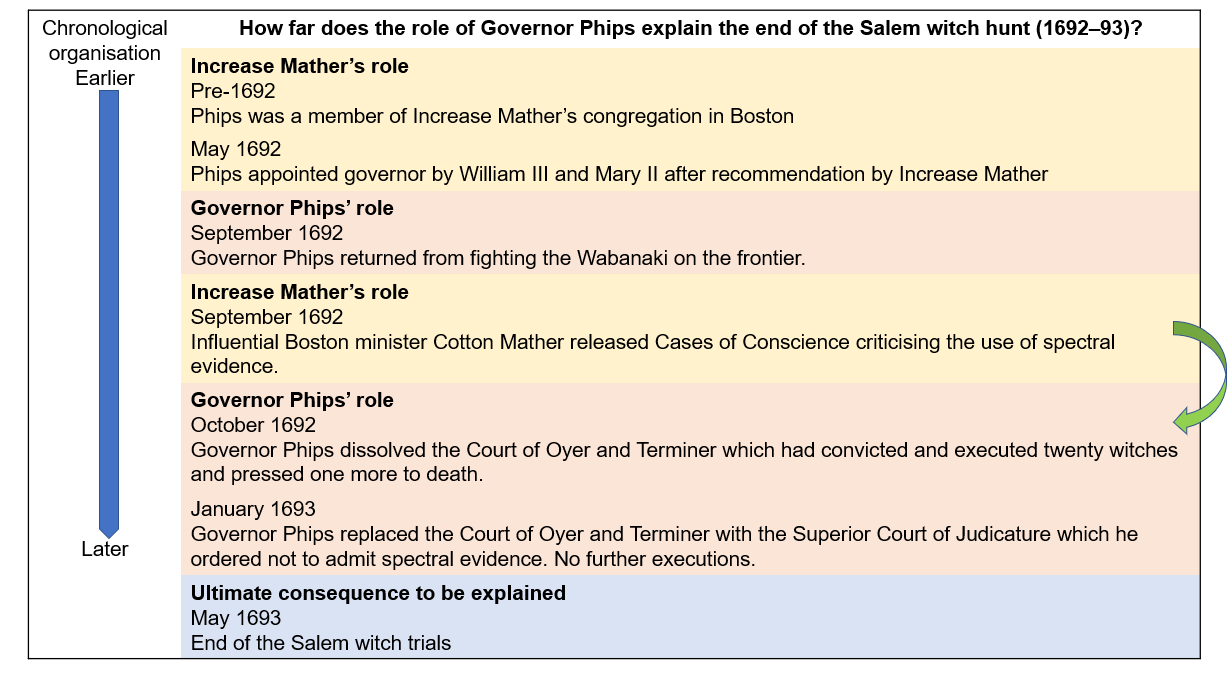

A further cause the students might include in their explanatory arguments could be the increasingly loud and convincing campaign led by more moderate and influential Puritan ministers – most famously Increase Mather. From the comparative safety of Boston, men such as Mather began to publicise arguments against the admission of spectral evidence helping to convince Phips, who was a member of Mather’s congregation, to change tack.

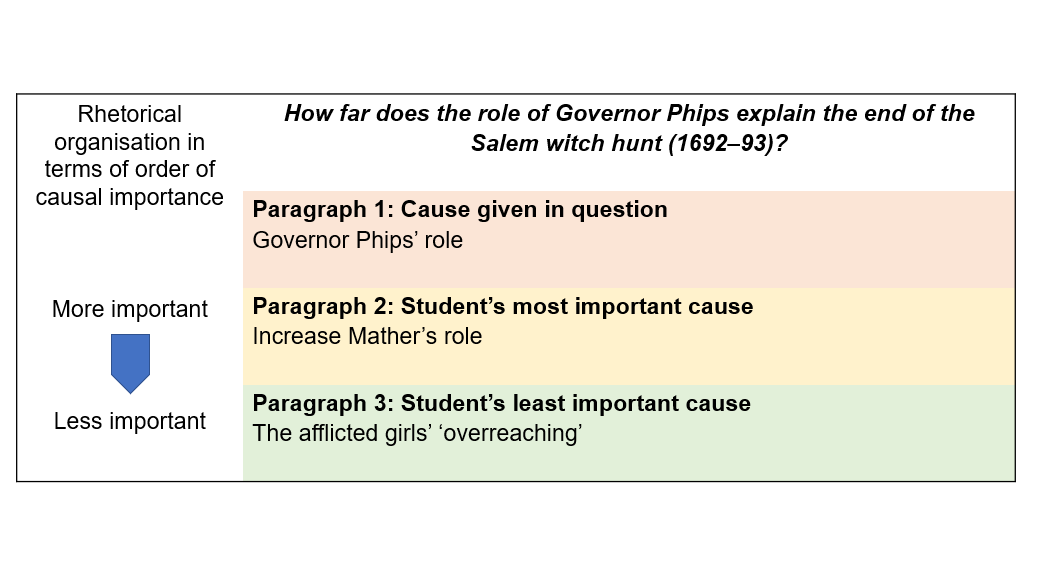

For our purposes here, let us limit ourselves to these three causes of the end of the hunt. Teachers might instruct students to adopt the following essay structure;

Introduction

One reason why the Salem witch hunt ended in 1693 was…the intervention of Governor Phips…

Another reason why the Salem witch hunt ended in 1693 was…the ‘afflicted’ girls’ ‘overreaching’…

A final reason why the Salem witch hunt ended in 1693 was… influential figures in Boston criticising the admission of spectral evidence…

Conclusion

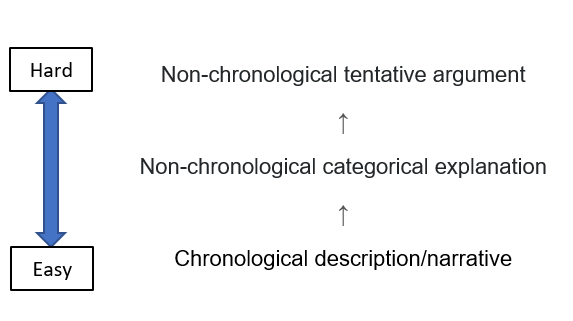

These frames are an example, I think, of how Australian genre theory has influenced literacy instruction in English secondary schools – albeit often in a bowdlerised, indirect, and uncredited way.[iii] At the very least, these scaffolds seem to have evolved in parallel to some genre theorists’ strikingly similar recommendations. Such suggestions include students starting paragraphs in ‘categorical explanations’ with ‘numeratives’ and a clear ‘hyper-theme’ such as ‘A second reason was (insert cause here)’.[iv] The rationale for such modelling is that it highlights for students the engendering or creation of cohesion and structure in texts.

Encouraging students to structure their extended writing coherently is clearly a laudable aim and I am not suggesting that some scaffolding, used judiciously, should not be used to this end. I do think, however, that there is an issue with these particular frames which seem at best only generically applicable to explanation in all ‘non-fiction’ writing. They present historical explanation as of essentially the same order as explanations in other disciplines where there might not be the same disciplinary conventions demanding one argues the relative importance of causes. Such frames, for example, might be perfectly appropriate for reporting why fires burn: ‘One reason is a source of heat…’. ‘Another reason is fuel…’. ‘A final reason is the presence oxygen…’. What matters in the fire example is that all of these causes are necessary in combination, not whether one is more important than the other.

But in a historical causal explanation a lack of attentiveness to the specifics of the discipline, reified in frames such as ‘another reason why was the girls’ overreaching…’, will almost always have a deadening effect. What most historians care about are problems such as whether the girls’ overreaching was more important than Phips’ return or not.

It is accepted by many historians that the main driver of a causal argument is the prioritisation of causes in terms of relative significance into some form of ‘pecking order’[v] or ‘hierarchy’[vi]. In doing so, these historians suggest one should aim to argue what the most important cause was. Carr perhaps most forcibly encapsulated this view regarding the typifying characteristic of historical causation;

The true historian, confronted with this list of causes of his own compiling, would feel a professional compulsion to reduce it to order, to establish some hierarchy of causes, which would fix their relation to one another, perhaps to decide which cause, or which category of causes, should be regarded ‘in the last resort’ or ‘in the final analysis’ (favourite phrases of historians) as the ultimate cause, the cause of all causes. This is his interpretation of his theme; the historian is known by the causes which he invokes…every historical argument revolves round the question of priority of causes.’[vii]

According to historians such as Hewitson, without such ‘ordering of ‘causes’ according to their salience or significance in respect to the question posed’ causal argument ‘itself would not be possible’. [viii]

If we accept this then while ‘another reason’ provides structural coherence it is completely stultifying to causal historical argument. In this sense I see starters such as ‘another reason why’ as a stark manifestation of a dangerous mentality that tends to view ‘the literacy’ as ‘a skill’ somehow disconnected from ‘the history’.[ix] In this instance, the desire to emphasise the importance of structure (‘the literacy’) might disable students from arguing the relative importance of causes (‘the history’). In particular, the frames might blinker the student from the fact that some historians a) use explicit language to argue the relative importance of causes and b) might rhetorically organise their overall text in such a way as to perpetuate their overall causal arguments.

Let us return to our example of the Salem witch craze’s loss of impetus. Historians in this historiography have often displayed the ‘professional compulsion’ described by Carr to prioritise their causes. For example, after outlining and explaining the role of less important causes Chadwick Hansen emphasised that, in his view, the girls’ ‘overreaching’ was the most important cause in the craze ultimately fizzling out;

But most important of all, as the witch hunt spread and the accusations flew, people were accused whom nobody could think guilty.[x]

Here, Hansen emphasised his argument by building toward the most important cause and indicating it clearly. A historian might structure their overall writing this way, perhaps beginning by arguing the limitations of existing arguments and thus preparing the reader for the clear statement and elaboration of the historian’s main thesis regarding the most important cause.

Frances Hill instead opted to emphasise what, from her perspective, was most crucial in ending the craze (the campaign in Boston against the Court of Oyer and Terminer’s admission of spectral evidence led by Increase Mather) by leading with the most important cause.

A huge backlash ended the witch-hunt. The single most important element in that backlash was an essay composed by Cotton Mather’s father, Increase called Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits Personating Men.[xi]

As both these examples show when arguing the relative importance of causes historians in the historiography of Salem might use the organisation of their text as an argumentative tool. Some also use clear language to indicate their overall argument in this regard. Both of these possible articulations of argument are shut down by prescribed essay structures based on starters such as ‘another reason why…’ which either imply the causes are of equal importance or even worse still might suggest to the student that prioritisation is not required at all.

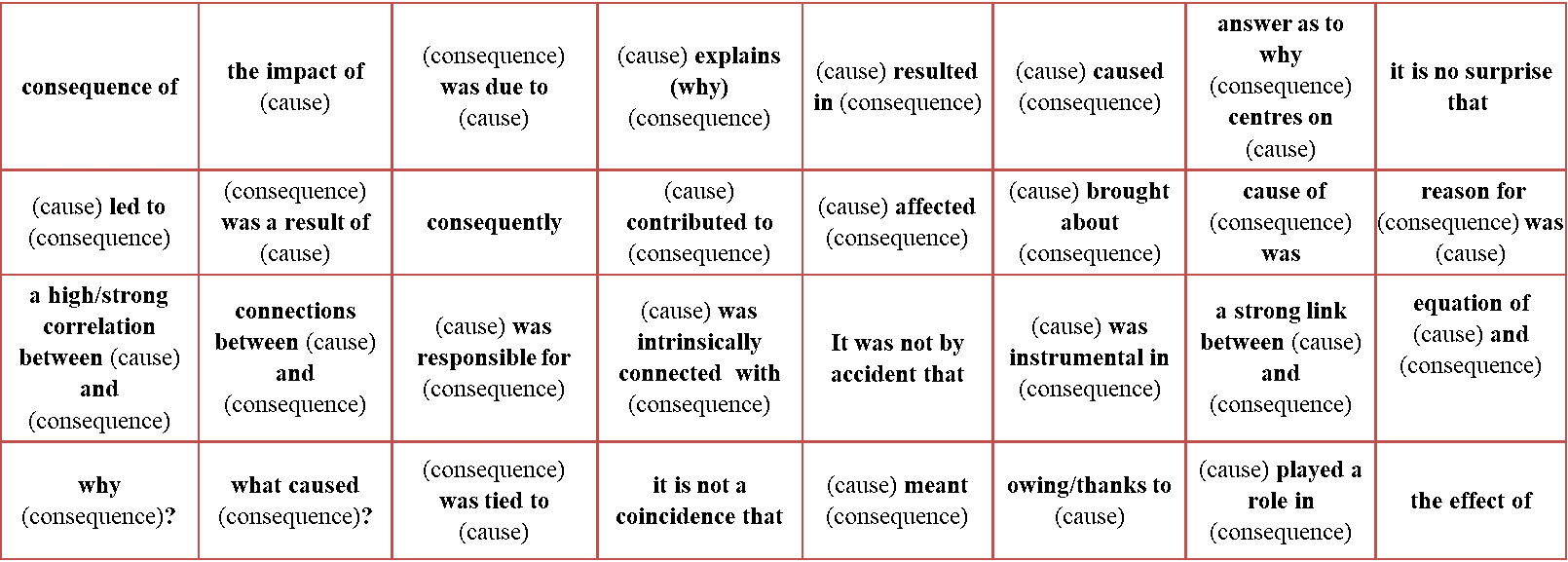

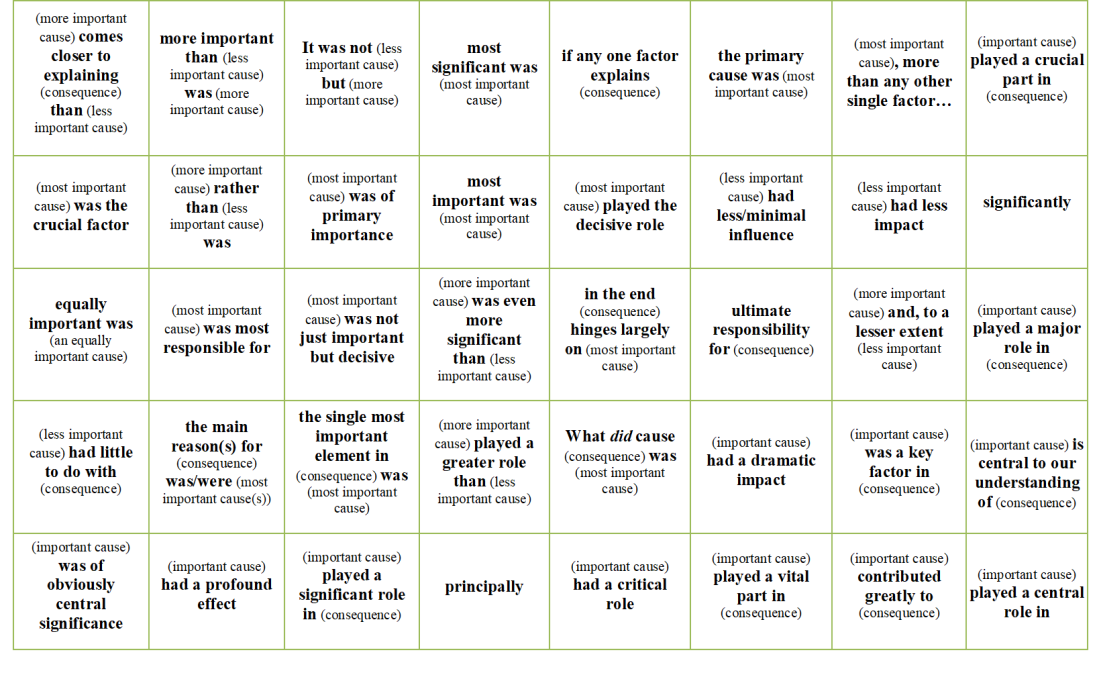

I have been trying to identify the specific language historians of Salem such as Hansen and Hill use in their causal arguments. I select particularly argumentative extended extracts to read with my class and then I model the authentic language the historian used. Below you can see some of the ‘chunks’ I have identified so far.[xii] Chunks such as these might be used to encourage students to think about the prioritisation of causes and how to articulate this argument at the paragraph- and overall essay-level.

The key here though is that ‘the literacy’ is not a bolt-on. First, the language is introduced in the context of a wider causal enquiry and read in its original argumentative context so the students can see it in its natural habitat. (That is why the chunks below should not be considered an ‘off-the-peg’ resource because students studying other historiographies would be denied the opportunity to see how the historian actually deployed them.) Second, the teaching of language itself might make concrete to students that prioritisation is the driver of historical causal argument.[xiii] Ultimately, the history teacher needs to continuously reflect on the possible ramifications of teaching literacy as an isolated ‘skill’.[xiv] Otherwise, we might condemn students to procrustean structures that ignore the historical epistemology and contort, butcher, or kill students’ arguments.

[i] What follows is a critique of common sentence starters that I have either a) used or seen being used in my practice or b) seen shared on social media or sold on resource websites. I have not included images or links of the specific examples because I do not want to personalise any critique.

[ii] Pearson, Edexcel (2017). Advanced Level 3 GCE History, Paper 3: Theme in breadth with aspects in depth, Option 33: The Witchcraze in Britain, Europe and North America c.1580-c.1750 9H10/33 retrieved from https://secure.qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/secure/silver/all-uk-and-international/a-level/history/2015/exam-materials/9HI0_33_que_20170623.pdf

[iii]Carroll, J. E. (2017). ‘From divergent evolution to witting cross-fertilisation: the need for more awareness of potential inter-discursive communication regarding students’ extended historical writing’ The Curriculum Journal 28(4) pp.504-523

[iv] See, for example, Coffin, C. (2006). Historical Discourse: The Language of Time, Cause and Causation London: Continuum. p.126; Martin, J. R. (1992). English Text. System and Structure Philapdelphia, PA: Benjamins pp.454-456

[v] For example Counsell discussed the dangers of ‘bolting on’ literacy Counsell, C. (2004). Building the lesson around the text, history and literacy in year 7. London: Hodder Education p.4

[vi] Tosh, J. (2006). The Pursuit of History: Aims, methods and new directions in the study of modern history London: Pearson p.154

[vii] Evans R. J. (1997). In Defence of History. London: Granta Books. P.158

[viii] Carr E. H. (1990). What is History? London: Penguin pp.89-90

[ix] Hewitson M. (2015). History and Causality. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p.161

[x] Hansen, C. (1988). Witchcraft at Salem. London: Arrow Books. pp.145-146

[xi] Hill, F (1996). A Delusion of Satan: The Full Story of the Salem Witch Trials. London: Penguin.pp.195-196

[xii]I describe this approach in far more depth here Carroll, J.E. (2016) ‘The whole point of the thing: how nominalisation might develop students’ written causal arguments’ Teaching History 162 pp. 16-24

[xiii] This is essentially James Woodcock’s idea. See Woodcock, J. (2005). ‘Does the linguistic release the conceptual? Helping Year 10 to improve their causal reasoning’ Teaching History 119, 5-14.

[xiv] See, for example, Evans, J. and Pate, G. (2007). ‘Does scaffolding make them fall? Reflecting on strategies for developing causal argument in Years 8 and 11’ Teaching History 128, 18-28.

Note that this approach turns an individual’s actions that point toward an explanation of the end of the trials (e.g. Phips closed the Court of Oyer and Terminer in October 1692) into a broad configurational abstraction that doesn’t actually explain very much (‘Phips’ role’). One way around this would be to create better abstractions that are explanatory (e.g. ‘Phips’ crucial role in ending the legal process’). Another way, probably in conjunction with a better abstraction, could be to focus on Phips’ actions in detail.

Note that this approach turns an individual’s actions that point toward an explanation of the end of the trials (e.g. Phips closed the Court of Oyer and Terminer in October 1692) into a broad configurational abstraction that doesn’t actually explain very much (‘Phips’ role’). One way around this would be to create better abstractions that are explanatory (e.g. ‘Phips’ crucial role in ending the legal process’). Another way, probably in conjunction with a better abstraction, could be to focus on Phips’ actions in detail.